What if our Collection Could Talk?

Botanic Garden - Leaflet

Leaflet 2020

Published June 6, 2021

Human-centered design is a way of engaging with the rapidly changing world, of taking care of a damaged planet and enriching the human experience. It is a practice of examining underlying assumptions and highlighting inequitable conditions. It is a means of making alternate futures tangible and testing new ways of operating in this world.

Here at Smith, through the Design Thinking Initiative, we have the opportunity to bring this design process from the classroom into practice through partnerships across campus. Design Thinking students employ new methods, mix unconventional ideas, and help to create a campus culture where these practices, methods, and ideas belong simultaneously to no one and everyone. As a result of a recent strategic planning process, Botanic Garden staff are exploring ways to make learning from the living plant collection a more inclusive and engaging experience for a broader audience, an exploration well suited to a design thinking framework.

In early conversations about a collaboration between Design Thinking students and the botanic garden Director Tim Johnson posited, “What if our collection could speak for itself?”—a provocation fitting Warren Berger’s definition of “a beautiful question—an ambitious yet actionable question that can begin to shift the way we perceive or think about something—and that might serve as a catalyst to bring about change.” During the second half of the 2019 spring semester, a team of four students in my interdisciplinary course, Critical Design Thinking, worked closely with Botanic Garden staff to explore and expand on the above definition of design offered up by one of the most celebrated designers in the United States.

Together with Manager of Education Sarah Loomis and Conservatory Curator Jimmy Grogan, the team decided to focus on how botanic garden curators were communicating plant information to garden visitors. Students investigated how visitors interacted with the six-inch-wide plastic labels that identified the plants. One visitor, having removed the label from the pot, held it up to the light and with a chuckle commented, “Yeah, I know nothing about this... this means nothing to me.” Students observed visitors craning their bodies sideways in order to read the information stating, “I can't really read it.” They found people were not sure if they were allowed to touch the plants or not. They observed people’s confusion about what seemed to be a QR code with no clear direction on how to access the information.

Suffice it to say, the labels weren’t really doing much to serve the majority of people visiting the gardens. Through conversations with Special Projects Coordinator Polly Ryan-Lane, the students came to understand that the information on the labels was intended to speak directly to the staff, and that the QR code on the labels was an internal tracking system, not a one meant for the public! It was clear that the labels were designed with a curatorial audience in mind and that they were failing to engage the general public.

In an interview with radio host Krista Tippet, Robin Wall Kimmerer, author, educator, and founding director of the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment, said, "One of the difficulties of moving in the scientific world is that when we name something, often with a scientific name, this name becomes almost an end to inquiry. We sort of say, well, we know it now. We’re able to systematize it and put a Latin binomial on it, so it’s ours. We know what we need to know... It’s such a mechanical, wooden representation of what a plant really is. And we reduce them tremendously if we just think about them as physical elements of the ecosystem... Science asks us to learn about organisms. Traditional knowledge asks us to learn from them."

This sentiment gets to the heart of the disconnect the students discovered between the goal of more deeply connecting audiences with plants and the primarily scientific ways in which information about the collection is communicated. The existing labeling system delivers on the earlier definition of design to communicate clearly, but only for a very narrow audience. Human-centered design asks us to examine a design through the experience of everyone that interacts with it.

After spending a significant amount of time getting to know the collection, students learned about the many unique characteristics of each plant species. They discovered that each of the more than 3,000 plants in Lyman Plant House had something to say. As stated in their final presentation, “Each of those plants has a story. Our task was to make sure those stories were told.” All of this led the students to reframe their prompt as, “How might we use labeling and signage to educate and engage visitors?”

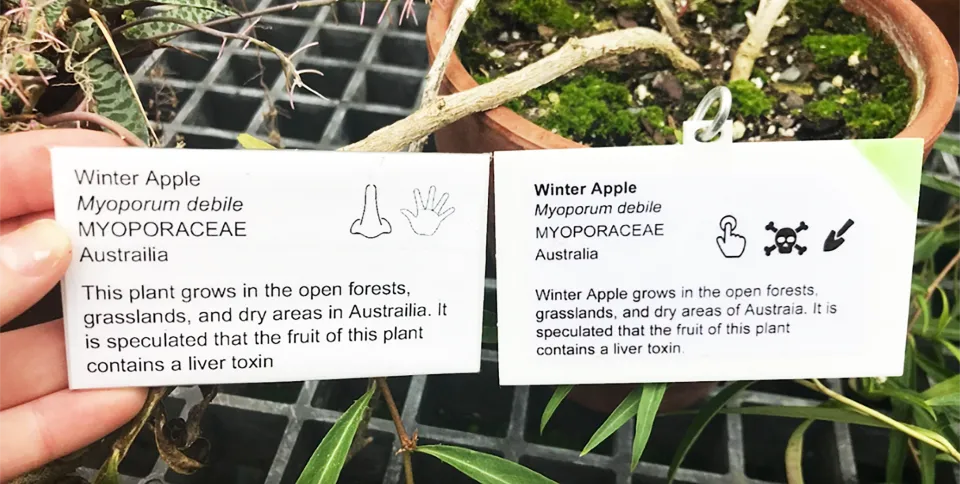

Having honed in on this framing of the challenge, students began prototyping alternative label solutions. Their first prototype visually favored the plant’s common name while retaining the Latin name as secondary information. They added small facts and stories and introduced an icon language to indicate if you could interact with the plant by smelling or touching it. For example, the Chinese silk plant label boasted, "The stems have strong fibers that do not rot and are used to manufacture textiles. It is also used to prevent miscarriages during pregnancy." They moved the inventory code to the back of the label in order to remove any confusion about its being a QR code intended for the public. They received good feedback on the short anecdotes and icons they were using, but they had not addressed the craning of the neck to access the information. Their second prototype shifted the format to a business card shape that could be read easily. The students then gathered feedback through passive comment boards placed in the conservatory, by interviewing garden visitors, and by bringing their new designs into public spaces and asking folks to interact with the different label iterations.

In their final prototype, students designed a label to be as beneficial to visitors as it was to horticultural experts and botanic garden staff. The label’s mounting system allowed it to slide into the potting mix and hang over the edge of the pot so as not to be lost in the foliage of the plant. Its hinged attachment to the stake allowed for the tag to be easily flipped by staff to access inventory information that was of no use to garden visitors. The labels were accompanied by signage that explained the label system. Through visitor testing, the students determined that the labels were most useful when installed level with the plants themselves. The project culminated with their prototypes being installed in the “testbed” at the conservatory. Students saw their work as laying the groundwork for a potential redesign by the botanic garden of the labeling system, driven by the insights gathered by simply engaging the audiences the garden hopes to better engage.

This project demonstrates the simple but profound power in observing and understanding the human experience. We all too often accept things as they are, simply because that is the way they have always been. Human-centered design is a participatory, iterative, inclusive, and cocreative process. If we’re going to deliver on Smith’s mission of “developing engaged global citizens and leaders to address society’s challenges,” a methodology that develops the agency to make change and take action is an essential educational tool. Thanks to the generous support of the botanic garden staff and members of the community, these students had the invaluable opportunity to apply this practice and cultivate these critical mindsets. Emma Eagle ’22, one of the students who worked on this project, commented in an evaluation of the class, “I think a lot of people accept the world the way it is just because that’s the way it is. This course taught me that anybody can look at something in this world and make a change.”

The student team who created human-centered label prototypes at Lyman comprised Annina Van Riper ’19 (linguistics and philosophy), Barb Garrison ’21 (engineering science), Emma Eagle ’22 (undecided), and Matlhabeli Molaoli ’22 (biochemistry and anthropology).