A Smithie in London

Botanic Garden - Leaflet

Leaflet 2020

Published June 6, 2021

Before coming to Smith College from my hometown of El Paso, Texas, I had never visited a botanical garden. In fact, it was only a couple months before arriving in Massachusetts that I found out such things existed! The tall trees and forests I saw on my very first drive to campus from Bradley Airport was all it took for plants to catch my attention. I was introduced to Smith’s botanic garden during the Bridge Pre-Orientation Program for students of color, when I attended a propagation workshop at Lyman Plant House. I enjoyed the work- shop so much I decided to take the course Botany for Gardeners the spring of my first year. With the guidance of Gaby Immerman, the botanic garden’s landscape and education specialist who teaches the Botany for Gardeners lab, I slowly became more and more involved with our botanic garden, first in work study via my AEMES scholarship (Smith’s program that provides first- and second-year students from underrepresented and low-income backgrounds with on-campus research opportunities), then as a summer intern. The more time I spent with the botanic garden staff, the more I learned about the different ways I could work with plants and what careers I could possibly make with them. During my junior year I left Smith to study abroad in Paris.

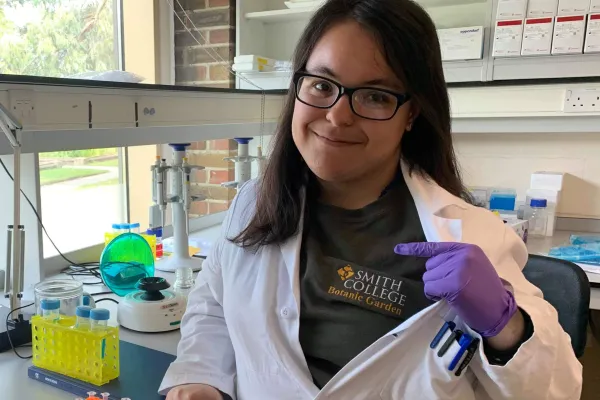

I am a biological sciences major here at Smith and I follow the ecology and conservation track. After spending a year in Europe, it became clear to me that concluding the spring semester with a summer internship would be the perfect way to end my time abroad, so I decided to apply for the botanic garden’s internship at the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. Before I knew it, I’d been selected as a recipient and was sitting in the Eurostar from Paris to London. The Kew internship gave me an opportunity to put the laboratory concepts and techniques I had been taught in class into real practice. While working at the Jodrell Laboratory I was able to interact with and learn from other researchers while further developing my lab skills.

For my research project I worked with Dr. Jim Clarkson, a member of the Plants and Fungal Trees of Life Project (PAFTOL). The goal of PAFTOL is to generate and compile DNA sequence data for one representative of all 14,000 plant genera and 8,200 fungal genera. Dr. Clarkson and I spent the summer at Kew working with the Apiaceae family, which includes well-known plants such as carrots, celery, and parsley.

The DNA extraction process was the first part of my research. I was given hundreds of small envelopes, each with a portion of an herbarium sample. The Kew herbarium houses a collection of 7 million plant specimens representing 95% of all plant genera. Although some of these plants are more than 100 years old, they still preserve genetic material that we can extract in the laboratory. Once I was able to fit those dried plant samples into small test tubes, I began the extraction method which would isolate their DNA. Two days of work would produce a pellet the size of a cupcake sprinkle that contained that specimen’s whole genetic identity. The second part of my summer was library preparation. This process began with using microscopic magnetic beads that would attach to DNA strands and allow me to select certain segments that would be easy to sequence. These strands would later be made into DNA libraries, which are amplified versions of those selected genes, made easier to read by the sequencer.

A couple of weeks before my time was up, I finished working through the Apiaceae material I was given to extract, so I moved on to the families Proteaceae, Pittosporaceae, and Araliaceae . This time however, I borrowed samples from the DNA bank. Kew is the owner of the world’s largest DNA bank; it contains about 48,000 samples of genomic DNA kept in cold storage at –80oC. Borrowing samples from the bank allowed me to skip the DNA extraction step and go straight into library preparation. By the end of my 10 weeks at Kew, I had extracted and or prepared just over 200 specimens for DNA sequencing; these will eventually be used to add into the ever expanding plant tree of life.

The most mind-blowing part about my research is that I was working with tiny drops of liquid yet, the farther I progressed, the more genetic information those small drops revealed. Knowing that if something were to happen to those tiny droplets it would mean that I would lose weeks’ worth of work felt like a lot of pressure, but Dr. Clarkson constantly as- sured me that science is all about making and learning from our mistakes, and this allowed me to continue with my work confidently.

At the Jodrell Laboratory I got to work with people who have so much experience and knowledge to share. I’m particularly thankful to my supervisor and mentor James Clarkson, who managed to teach me so much in such a short amount of time while also giving me time and space to learn from my mistakes. My favorite part about the PAFTOL team is that every other Thursday we would go out for lunch and take time to interact with one another outside of work. During the annual Kew science festival, the PAFTOL team ran a “DNA factory” where kids could learn how to extract DNA from a strawberry.

Spending a summer at Kew was a life changing experience. In addition to what I learned in lab, I got to live in a whole different country that, up until then, I had only read about in books. While in London I was able to travel around and see a lot of what the city has to offer. I got on the London Eye, passed under many famous bridges while on a tourist boat, walked on the Abbey Road crosswalk, and my favorite, I visited Warner Brothers Studios where the Harry Potter movies were filmed—my childhood dream come true! Those visits were made financially accessible thanks to the generous stipend that myself and my fellow intern Adrianna Grow ’20J received from the Smith Club of Great Britain. Although I’m not sure what type of career in botanic gardens or public horticulture I will pursue, my experience with the Kew internship has made laboratory research into a very clear possibility.